Brutalism. You either like it or you don’t. Characterized by its rigid, monumental forms and the unapologetic use of raw, exposed concrete, brutalism is more than just an aesthetic; it embodies a distinct architectural philosophy. This article will delve into the origins of Brutalism in the period of post-war Western Europe, trace its controversial global rise over the years, examine the factors contributing to its decline, and explore its complex and never-ending legacy in the architectural landscape.

Figure 1: Hirshhorn museum, Washington, D.C. Christophe Laurenceau via Unsplash.

What is architecture?

Originating roughly 10,000 years ago, architecture is born out of the human instinct for survival and shelter. Architecture, defined as “the art and technique of designing and building” (Collins and Ackerman, 2022), is a means of expression and function. There are many possible functions of architecture, such as ritualistic means, urban housing, and artistic expression.

In architecture, many different styles coexist with each other. A category to sort architecture styles is from their balance of form and function. For example, art nouveau—known for its use of organic motifs, sculpted steel, and mosaic or stained glass work—prioritise form more than function. On the other hand, functionalism, just like its label, is often described with the phrase “form follows function”. In between this scale lies brutalism.

The foundations of brutalism

Defining brutalism

Brutalism is easily identified by its rigid edges and monotone colors resulting from the high amount of concrete that is used to build them. Since its creation, brutalism has been designed with the use of raw concrete in mind as concrete matches brutalism’s core philosophy.

Brutalism is valued for its commitment to using the rawest materials; this should be recognized as its most defining and memorable principle. Because of this, brutalism is viewed as both an ethic and an aesthetic. To the casual observer, brutalist architecture is often judged solely by its appearance—its rough, stark exterior—without understanding the deeper ideology behind the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of its ethical foundation. Practitioners of brutalism believe that when buildings are stripped down to their very core—to their rawest state—time and space don’t affect them anymore. They believe that a building’s beauty is shown through its structure, the explicit exposition of its construction methods, and utilising ‘true’ materials; this is when the public is able to judge them honestly.

Figure 2: Plaza de la Independencia, Madrid. Pelayo Arbués via Unsplash.

Origins

Postwar Western Europe

During the postwar era, many citizens lived in rough conditions and were placed in slum housing. At the time, slum housing was a quick but temporary solution that housed many impoverished people by placing them in overcrowded housing that did not have the necessary amenities for healthy living.

Figure 3: Saar story. Iron and steel industry reaches postwar high. Via getarchive.net.

As a result of this crisis, many architects joined together to create an urban plan to house citizens quickly in a more modern landscape. These planner’s goal was to instill modernist ideals, which was a style that focused on experimentation, individualism, and breaking through from traditional forms (Modern San Diego).

Modernism was a fast growing movement in urbanisation plans with many works appearing at that time, such as Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation in Marseille.

Figure 4: Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation (Esakov, 2019)

Le Corbusier, a visionary of architecture and still one of the present times’ most well-known designers, was a pioneer for modernism. His works can be found all around the world and 17 of his works have been credited as world heritage buildings by UNESCO. As Le Corbusier designed the Unité d'Habitation, he mainly worked with concrete as its exterior and because of the great amount, he coined the word béton brut as a term for raw concrete in architecture (Choay, 2025).

Other than that, one of Le Corbusier’s footprints in history is his advocacy for better urbanscapes for citizens as a member of the CIAM (Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne) in France. The CIAM, established in 1928, had formed strict regulations and rules when designing their urbanisation plans that the group had developed over the years. It had been discussed that urbanisation should not be guided by existing aesthetic ideals but instead by practical and functional needs. The unplanned division of land, often caused by private sales, speculation and inheritance, leads to disorganised urban growth. To resolve this, a collective and methodical land policy is necessary to ensure cities develop in a structured and purposeful way. The CIAM had established this plan of a ‘functional city’, with the objective of spreading this modern movement internationally.

Uprising against modernism

After the disruption of the war died down and urbanisation had become relevant again, unsatisfied with the ‘outdated’ ideal of the CIAM came together a group, team X. Team X, which was established in 1953, sought to construct based on their current situations and to not stray away from postwar realities. They believed that architecture and urban design should respond to the needs of the community during the postwar world, the change in city structure, and cultural aspects of the time. This is the origin of brutalism. “By specifically addressing the issues now prevalent in the motor age such as a need for motorways, and embracing the possibilities that this age brought, such as the potential for larger, more diverse and functionally-situated areas, the urban landscape would become more livable” (Reynolds, 2015).

Figure 5: Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAI) via Wikimedia Commons

Brutalists' wish in building was to create a community oriented ‘streets in the sky‘, which emphasises their care in designing community centered housing. This philosophy of brutalism was an obvious opposition towards modernism aiming to ‘reject refinement’ and to show the beauty of buildings when stripped down to their core. And coincidentally, with the disruption of war emerged the scarcity of wood and steel—the main components of designs at the time. This had pushed architects to use concrete, which contributed to brutalism’s rise.

Two leading innovators in Team X, Alison and Peter Smithson, are recognized for having designed the first brutalist building, the Secondary School at Hunstanton in Norfolk in 1954. They mark the start of the brutalist era in the 1950’s and were core members in establishing Team X’s philosophy of ‘low-cost modularity, material focus, and purity and, most importantly for the Smithsons, buildings that reflected their inhabitants and location, ones that fostered community’ (Goodwin, 2020).

Figure 6: Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens, 1972. stevecadman via Wikimedia Commons.

Although years have passed since the war, during the 1960s, citizens still grappled with the unfortunate housing crisis. Fortunately, brutalism was a quick fix for that. With its low-cost and high amount of raw concrete, paired with team X’s philosophy of community, brutalist housing was built in a matter of months and housed many in need. Houses that had a concrete exterior were also reported to be easier to manage through rain and fog.

Other than physicality, citizens were out seeking a symbol of strength; a symbol for rebuilding. With its strong rigid exterior, brutalism had become a symbol of the nation's power. Many landmarks, government institutions, and educational institutions were destined to have this concrete exterior because of its low-cost but strong build. This made masses favour brutalism in its ability to reflect the postwar mentality in a way that modernism couldn’t.

Reyner Banham: New Brutalism

Reyner Banham was important in defining and articulating the concept of the New Brutalism, both as a critic and theorist. In his 1955 essay “The New Brutalism”, Banham identified the movement not simply as an architectural style, but as an ethical approach to design. It was through Reyner Banham’s words that defined brutalism for the future generations: ‘1, memorability of an image; 2, clear exhibition of structure; and 3, valuation of materials as found’ (Banham, 1955). He emphasized that New Brutalism was not about raw concrete alone, but about "an architecture that reveals its structure, materials, and purpose without disguise." Banham praised projects like Alison and Peter Smithson’s Hunstanton School for their refusal to hide structural elements or materials, showcasing steel, brick, and services in a direct and unadorned way.

This new and rebuilt view of brutalism had been backed by Alison Smithson for her work of a small house in Soho. Before she had labeled it brutalist on her own accord, it had been described as ‘warehouse aesthetic’. Right until—in her own words—she had said that, “… had this been built, it would have been the first exponent of the New Brutalism in England, as the preamble to the specification shows: ‘It is our intention in this building to have the structure exposed entirely, without interior finishes wherever practicable. The contractor should aim at a high standard of basic construction, as in a small warehouse’.”

Soviet Union

As the Soviet Union also faced struggles in rebuilding after the war, they started planning their future urban plans around the same time as Western Europe started. In history, the Soviet Union is known for their frequency of changing styles, depending on who is in power at the time; from the constructivist architecture in the 1920’s, classicism in the 1930’s, to Nikita Khrushchev's Khrushchevkas style that had stayed long after the 1950s. It was after this that Leonid Brezhnev’s coming to power in 1964 entailed a loosening of central control which led the Soviet Union to express emerging modern identities through architecture. This change in attitude made a gap for the Soviets to fill in how they were to continue in urbanization.

Just like Western Europe, they had many modernist designs around the time that did not fit their values. They kept experimenting, again and again. Their determination and efforts in designing unique sculptures and forming their own identity as a nation kept them from following trends in other countries.

Figure 7: Eduardas Chlomauskas, Vilnius, Lithuania (Guillaume Speurt)

In the 1970s, though it was unknown then, the Soviet Union had communication with Europe and was well aware of the emergence of brutalism there. This is when their experimental works started showcasing more and more brutalist features, from the rigid, raw concrete to the philosophy. They had created their own twist on the style: Soviet brutalism. For the Soviet Union, other than a symbol of strength, brutalism also gave another aspect that other styles couldn't: uniformity in design and a focus on functionality.

Spread through Asia

After brutalism had established itself in European countries, it spread to other nations in a domino effect. Many architects from Europe and the Soviet Union were brought to Asia in an attempt to change the culture and local history in many Asian countries, mainly central Asia.

Although the Soviets tried to print their style, local architects in Asia had prevented them from completely changing the landscape, but they agreed to work together instead. This combination of local and brutalist Soviet architecture influences created a unique mix in designs that have become famous in their own right. The main appeal in brutalism for Asia, was again, its symbol of strength. For central Asia, it signified their independence and freedom after the war.

Figure 8: Secretariat Building, Chandigarh by Le Corbusier. Sanyam Bahga via Wikimedia Commons.

A decade after India gained independence, the nation was targeted by the British to create their own urban projects in the land. At the time, there was an underdeveloped land that the prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, sought to urbanise. He had plans in hiring American architects, but they had stepped down right before (Atanassova, 2022). That is when Le Corbusier came to take over the project. Though Le Corbusier was not as hands-on in this project as his others, it can’t be argued that he had a major influence in its planning. When designing the work, he changed the original plan to one more similar to his other works by using beton brut, his signature style. He made sure that the land’s buildings were all sturdy, symmetrical structures just like his other works. With Le Corbusier’s personal touch, this city of Chandigarh has now become a known brutalist site in the architecture sphere and is widely appreciated until now.

Another nation that has been hit by the brutalist influence by the western nations is Japan. By August 1945, 19 percent of all residential buildings in Japan were destroyed by aerial bombings—44 percent if only urban areas were considered. Rather than rebuild the housing stock, the Japanese government chose to focus on economic recovery first. As many citizens moved to capital cities, with the small amount of land Japan has, this event had made land prices rise drastically. With rising prices, many couldn’t afford to live in detached houses. This is when apartment blocks in Japan gained popularity. Apartment blocks lent the people a cheaper alternative to housing while still living in more populated prefectures.

With impressions from the brutalists in Europe and the Soviet, Japan looked up to the efficiency in building low-cost concrete structures. Between communications with European architects, the Japanese learned to merge traditional with European and Soviet influences to create an experimental housing estate called danchi.

The Japanese danchi is Japan’s own interpretation of brutalist philosophy, focusing on the people-oriented community aspect while keeping the building costs low. Most danchis that were built around the time had a concrete exterior accompanied with the famous Japanese minimalism for its interior. Although small in size, together, it created a project that was loved by the citizens from its aesthetics to its practicality.

Figure 9: Kawaramachi Danchi. Via Wikipedia Commons.

Initial reception

Brutalism had spread worldwide as a symbol of strength and low-cost build. Many nations favoured this style because of it. It had an impact on the citizens no other style could; with its rough and harrowing exterior, it depicted an accurate postwar reality and left a mark on society. As the years passed, it satisfied the people with how fast it could shelter many and people had started to appreciate its philosophy of functionality and design.

It wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows, however; a few years after the housing crisis started to subdue, people and their judgement of brutalism also started to change. Free from the idyllic glass that people had seen, realization spread and brutalist buildings started to be scrutinized because of their exterior. During this time, not many citizens enjoyed the look of its harrowing and monotonous exterior, it had quickly become a style that was hated and scrutinised. Many called the large structures ‘alienating’. ‘Widely perceived as architecture so manifestly bad, so obviously against natural human scale, value, and aesthetics that it was barely architecture at all.’ (Hopkins, 2023).

The brutalist ethos

Figure 10: High Angle View of Blocks of Flats, Kyiv, Ukraine. Mykhailo Volkov via Pexels.

Ideology

The brutalist ideology is to find the beauty of structure from the building’s own raw materials. Without any extra ornaments to distract the eye, that is when people can judge a structure objectively without the bias of time. Its focus on function over aesthetics creates useful structures that efficiently do what they are built to do.

Opposing styles

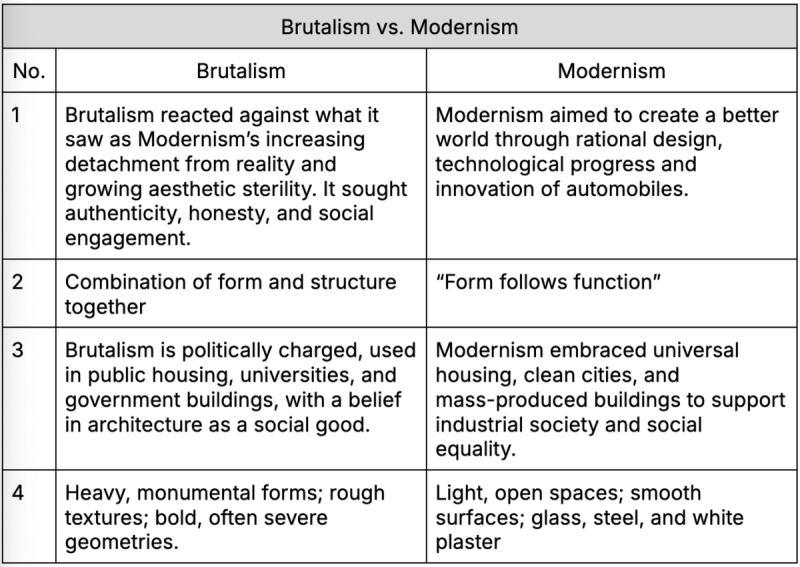

Table 1: Characteristics of brutalism and modernism.

Architectural language of brutalism

Inspiration

As brutalism’s philosophy grows throughout the years, architects that continue to spread this style are sure to gain inspiration from other styles. With merging styles, architects must always look back on what had inspired the original brutalists in the first place.

Figure 11: Modernist example, Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Japanese wabi-sabi

The tale of wabi-sabi architecture is easily told by its own name. With the words wabi, defined as ‘recognizing beauty in humble simplicity’ and sabi, ‘suggests that beauty is hidden beneath the surface of what we actually see, even in what we initially perceive as broken’ (Itani, 2021).

Commonly featuring natural colors, materials, and the play of light, wabi-sabi gives a comforting feel for its inhabitants. Most structures use earthy tones and dim atmospheres to emphasise its connection to nature and core. It also features major aspects of minimalism, with its choices in experimenting with empty space. Wabi-sabi had inspired brutalism, appreciation of natural and raw materials and celebration of simplicity.

Figure 12: Kyōto-Ginkaku-ji.

The philosophy of wabi-sabi is one that encourages to find the beauty in a structure's imperfection, no matter how unsymmetrical, imbalances, or clashing colors it holds, it is that sense of awkwardness that creates beauty. In some buildings, that sense of misalignment and uncertainty in the structure could seem like an accidental feature, but wabi-sabi architects give more purpose in each ‘wrong’ measurement more than what other styles could imagine. But scrutiny is a given for all structures, and wabi-sabi isn't an exception. Like brutalism, it too was criticized for its ‘unique’ exterior.

Cubist architecture

In the 1900s, cubism was seen as a revolutionary style that had diverted expectations of what architecture would have developed into. ‘Cubism had a significant impact on modern architecture. Many architects began to experiment with new, more abstract forms and shapes.’ (Amber, 2022). It was a very sudden shift from the usual classical works and styles such as colonial revival and Italian renaissance revival—which both feature aspects from the past in a new light.

Figure 13: Elišky Krásnohorské 123/10, Praha-Staré Město. Dennis G. Jarvis via Wikimedia Commons.

This style emphasises abstract structure, and its impact on modernism was extraordinary. Brutalist architecture also emphasizes geometric clarity, but in a more stripped-down way. Brutalists were influenced by the Cubist idea that form itself can be expressive, even without ornament. In addition, Le Corbusier’s early work was heavily influenced by Cubist visual art and Purism, which is how his style came to be. His Unité d'Habitation, bridges Cubist abstract ideals with raw, monumental form.

Decline of brutalism

Figure 14: St James Centre, Edinburgh. (Chris Malcolm)

Unfortunately, brutalism’s rise to stardom did not last long. The decline of brutalism began in the late 1970s and accelerated through the 1980s, driven by a combination of aesthetic backlash, political change, and practical concerns. Contrary to its ideology, many people have started seeing brutalism as ‘alienating’ because of their large, looming concrete structures. Seeing these structures next to the traditional home, for most, it struck a sense of disgust towards it.

Public perception turned negative as many brutalist buildings, especially housing projects, became associated with urban decay, crime, and institutional coldness. As postmodernism gained popularity, with its utilization and focus on ornamentation, brutalism was increasingly viewed as outdated, oppressive, and inhumane. ‘Widely perceived as architecture so manifestly bad, so obviously against natural human scale, value, and aesthetics that it was barely architecture at all’ (Hopkins, 2023, pp. 8-11).

Maintenance problems

Initially, architects believed raw concrete to be easy to source, build, and design with. As it is not bright in color, it was not necessary to maintain it from stains and moderate decolorization. It was believed to be easy to maintain as it survives through hard impacts, scratch resistant, and easy to clean.

But after a few years, it proved vulnerable to weathering, staining, and corrosion—especially in damp or polluted environments. Over time, many brutalist buildings developed cracks, water damage, and discoloration, giving them a prematurely aged or neglected appearance. Unlike traditional materials like brick or stone, concrete is difficult and costly to repair or restore once damaged. These maintenance problems contributed to a growing public perception of brutalist buildings as cold, decaying, and uninviting, accelerating their downfall.

1973 oil crisis

In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed an embargo against the United States in retaliation for the U.S. decision to resupply the Israeli military (Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute).

When the oil crisis caused energy prices to spike and triggered a global economic downturn, governments, institutions, and major supporters of Brutalist projects faced budget cuts. This led to a sharp reduction in funding for public housing, infrastructure, and monumental civic buildings. The price of oil skyrocketed and almost quadrupled normal prices. This significant event showed that there will not be sufficient supply of concrete to allow architects to build brutalism at the same rate.

As a result, the biggest selling point of brutalism—its cost-efficiency—vanished. Moreover, the energy crisis sparked a worry on energy efficiency and insulation, areas where exposed concrete buildings performed poorly. Brutalist structures were often cold and thermally inefficient, making them expensive to heat in a time of rising energy costs.

The present climate

The polarizing judgments of Brutalism in its early years continue to shape its status today, producing both a revival in appreciation and ongoing threats of erasure. On the positive side, Brutalist architecture is increasingly recognized for its historical and architectural significance, influencing contemporary designers who draw on its bold forms, raw materiality, and social ambitions.

Present brutalists that appreciate the works, persevere to defend these monoliths from demolishment. Institutions like the Victoria & Albert Museum have taken steps to preserve elements of Brutalist heritage, such as the Robin Hood Gardens, a seminal housing project by Alison and Peter Smithson. Despite these efforts, the building itself was demolished in 2018, a stark reminder of Brutalism’s contested legacy. Many Brutalist structures continue to face demolition, often dismissed as eyesores or impractical relics of the past, as highlighted in the widespread loss of works by architects like Paul Rudolph.

Neo-brutalism

A contemporary adaptation of original brutalism, neo-brutalism strives to become an entirely different style while paying homage to its roots. Neo-brutalism constitutes a modern design style that draws profound inspiration from the original Brutalist architectural movement of the 1950s to mid-1970s. At its philosophical core, neo-brutalism, much like its predecessor, champions functionality, honesty in materials, and a discernible social purpose. This design ethos inherently prioritizes simplicity and a deliberate departure from the overly sleek, polished, and often perceived as superficial aesthetics prevalent in much of contemporary design.

The style retains the raw, unpolished essence of brutalism but incorporates refined touches, modern features, and a broader aesthetic color palette, moving beyond the stark utilitarianism of original brutalism. This refinement often includes subtle additions of color, texture, and a greater emphasis on balance and proportion.

In cities like Seoul, new brutalism can be seen thriving and ever-growing throughout the years. “With tiled and textured finishes and flowing forms, some of the buildings documented by Olivier are more Neo-brutalist than brutalist. The commercialization of the style is evident… and these buildings seem more popular and numerous in the city than 20th-century Brutalism ever was.” (Baranyk, 2017)

In contrast to brutalism, neo-brutalism has been found everywhere in today's sphere, increasingly prevalent in residential design. It offers a unique blend of raw aesthetics with modern comfort. Perhaps most notably, neo-brutalism has made a substantial impact on digital design, influencing UI/UX, web design, and graphic design with its bold typography, contrasting colors, and raw elements.

Recent brutalist works

Chichu art museum

Figure 15: "Time/Timeless/No Time," by Walter De Maria, 2004 at Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima (Simon Noizat)

The Chichu art museum, designed by Tadao Ando and completed in 2004, is a striking example of how architecture can enhance and interact with art. Ando personally curated the museum’s permanent exhibitions, selecting works that explore the relationship between light and space. Each installation is displayed in a space specifically designed to emphasise the light of the artwork, showcasing collaboration between artist and architect.

At certain times of the day, sunlight enters from a cut in the roof and reflects off the polished surface to the gold-leaf rectangles on podiums around the room. Tadao Ando worked with the artist to design the space to fit with the artwork, orientating the room in order to catch the sun’s path; another example of site-specific collaboration between artist and architect. Tadao Ando transforms the museum itself into an extension of the art, creating an immersive experience for visitors.

Tate modern switch house

Figure 16: An Aerial Shot of the Tate Art Gallery in London (Ollie Craig)

The Tate Modern Switch House, completed in 2016 by Herzog & de Meuron, is a striking example of contemporary architecture that channels the spirit of brutalism while reinterpreting it for a modern audience. The Switch House embraces brutalist principles through its monolithic form, raw materiality, and emphasis on structure. The exterior features a textured brick lattice, which is similar to the rugged surfaces of traditional brutalist concrete while softening the visual impact compared to older works.

The building’s bold geometry and presence reflect the old brutalist ideology as a symbol of strength, yet its focus of light, circulation, and public space aligns with contemporary and modernist values of openness and accessibility. In this way, the Switch House stands as a neo-brutalist landmark.

A revival?

Although the style was monumental in its time, brutalism is now fighting tooth and nail just to have a place in today's society. It wouldn’t be honest to say that the style could go on without criticism following it closely behind, but with architectural tastes and trends constantly changing, it wouldn’t be surprising if new iterations keep expanding in the global circle. From proof from the rise of neo brutalism, it is possible for brutalism to be revived and to convince masses to view the style in a new light.

Nowadays, brutalist buildings are still targets for demolishment and though odds are stacked against them, brutalists around the world fight against it. Take this group established and led by a group of german brutalism advocates, #SOSBRUTALISM, which states that, ‘#SOSBrutalism is a growing database that currently contains over 2,000 Brutalist buildings. But, more importantly, it is a platform for a large campaign to save our beloved concrete monsters’ (Elser et al.).

Works Cited

Amber. “The Impact Of Cubism On Architecture.” 2022, https://www.forthepeoplecollective.org/the-impact-of-cubism-on-architecture/.

“archiweb.cz - Azuma House.” Archiweb, https://www.archiweb.cz/en/b/dum-azuma.

Atanassova, Elizabeth. “India's Overlooked Concrete City of Oz.” Messy Nessy Chic, 14 December 2022, https://www.messynessychic.com/2020/09/01/indias-overlooked-concrete-city-of-oz/.

Banham, Reyner. “The New Brutalism.” The Architectural Review, December 1955.

Baranyk, Isabella. “Korean Curiosity: Is Seoul Experiencing a "Neo-Brutalist Revival"?” ArchDaily, 25 April 2017, https://www.archdaily.com/869385/korean-curiosity-is-seoul-experiencing-a-neo-brutalist-revival.

Biber, James. “Brutalism: the language of evil. Why are nearly all Criminal Mastermind… | by James Biber.” UX Collective, 25 January 2022, https://uxdesign.cc/brutalism-the-language-of-evil-8be09f8c1e93.

“Brutalism Now.” Architecture Today, 27 November 2019, https://architecturetoday.co.uk/brutalism-now/.

“Brutalism: The Truth Behind London's Post-War Architecture | IWM.” Imperial War Museums, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/brutalism-the-truth-behind-londons-post-war-architecture.

Corbusier, Le. “Brutalist Architecture Movement Overview | TheArtStory.” The Art Story, 8 May 2020, https://www.theartstory.org/movement/brutalism/.

Dalrymple, Theodore, and Neave Brown. “Brutalist Architecture: Origins, Characteristics, and Examples – dans le gris.” Dans Le Gris, 16 November 2023, https://danslegris.com/blogs/journal/brutalist-architecture.

“Traditional Architecture V. Brutalism.” Mustardjobs, 11 January 2023, https://www.mustardjobs.co.uk/a-school-of-place-traditional-architecture-v-brutalism-fight/.

Elser, Oliver, et al. “#SOSBRUTALISM.” #SOSBRUTALISM, https://www.sosbrutalism.org/cms/15802395#about.

Esakov, Denis. Unite d' Habitation (1947-1952). Arch. Le Corbusier. 2019, Marseille.

Goodwin, Dario. “Alison and Peter Smithson: The Duo that Led British Brutalism.” ArchDaily, 22 June 2020, https://www.archdaily.com/645128/spotlight-alison-and-peter-smithson.

Heathcote, Edwin. “Soviet brutalist architecture explored: the ultimate guide.” Wallpaper Magazine, 13 November 2024, https://www.wallpaper.com/architecture/soviet-brutalist-architecture.

Henley, Simon. Brutalism in architecture, https://www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/brutalism.

“Hidden Architecture » Druzhba Sanatorium - Hidden Architecture.” Hidden Architecture », https://hiddenarchitecture.net/druzhba-sanatoriu/.

Hopkins, Owen. The Brutalists: Brutalism's Best Architects. Phaidon Press Limited, 2023.

Itani, Omar. “5 Teachings From The Japanese Wabi-Sabi Philosophy That Can Drastically Improve Your Life — OMAR ITANI.” OMAR ITANI, 23 April 2021, https://www.omaritani.com/blog/wabi-sabi-philosophy-teachings.

Ives, Mike. “Too Ugly to Be Saved? Singapore Weighs Fate of Its Brutalist Buildings (Published 2019).” The New York Times, 27 January 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/27/world/asia/singapore-brutalist-buildings.html.

Levanier, Johnny, and Tamara Milakovic. “Brutalism in design: its history and evolution in modern websites - 99designs.” 99Designs, https://99designs.com/blog/design-history-movements/brutalism/.

“Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations.” Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations - Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo.

Mitchell, Nancy. “A Brief History of Brutalism, the Architectural Movement Loved by Critics and Hated by (Almost) Everyone Else.” Apartment Therapy, 13 December 2016, https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/a-brief-history-of-brutalism-237571.

Nemirovsky, Gene. “Why Neo-Brutalism?. Most designers, who aren’t deserted… | by Gene Nemirovsky.” Medium, 20 October 2023, https://medium.com/@nemomakes/why-neo-brutalism-b1891990dd1b.

Parson, Meghan. “Remaking Brutalist Buildings — Hacker - Portland.” Hacker Architects, 10 October 2023, https://www.hackerarchitects.com/news/remaking-brutalist-buildings.

Salmon, Felix. “Concrete jungle: why brutalist architecture is back in style.” The Guardian, 28 September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/28/grey-pride-brutalist-architecture-back-in-style.

Sasaki, Ruth Fuller, et al. “Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 28 June 2006, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-zen/.

SCALE. “Tracing the Roots of Brutalism in Washington, DC.” SCALE, 28 November 2023, https://scalemag.online/architecture/tracing-the-roots-of-brutalism-in-washington-dc/.

Shanghvi, Dhwani, and Mrinmayee Bhoot. “Exploring Washington through 'Capital Brutalism' at the National Building Museum.” STIRworld, 11 November 2024, https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-exploring-washington-through-capital-brutalism-at-the-national-building-museum.

Stouhi, Dima. “A Rebellion Against Realism and Art: How Cubism Influenced Modern Architecture.” ArchDaily, 15 July 2022, https://www.archdaily.com/985450/a-rebellion-against-realism-and-art-how-cubism-influenced-modern-architecture.

Trunk, Jonny. “Alison and Peter Smithson.” Greyscape, https://www.greyscape.com/architects/alison-and-peter-smithson/.

“What Is Brutalist Architecture? Definition, Characteristics, and Examples.” The Spruce, 20 September 2024, https://www.thespruce.com/what-is-brutalism-4796578.

Williams, Glesni Trefor. “Revival of Brutalism: The Architectural Style Making a Comeback.” Sound of Life, 15 May 2023, https://www.soundoflife.com/blogs/design/brutalist-architecture.